While considering a subject for a project on data visualisation, in order to make the research as relevant as possible to my overall course objectives, I decided to focus on three prominent Russian artists of the early 20th century. Kazimir Malevich, Vladimir Tatlin and Alexander Rodchenko were all important figures in the Russian avant-garde movement of the 1920s. Each working in a variety of art disciplines, generally in the style of geometric abstraction, their work has been highly influential on many artists in the west throughout the 20th century, and they have been the subject of a considerable amount of critical writing outside of Russia. In order to trace the trends of the writing that exists about these artists, I used Google Books Ngram viewer, Google’s online search engine that allows users to search for the frequency of occurrences of particular words in a given language.

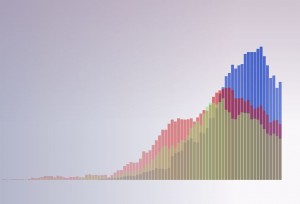

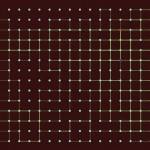

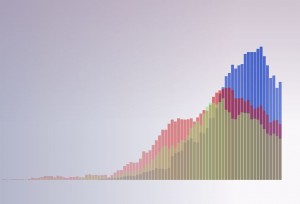

The diagram above shows the results of a search for the three names, in the English language corpus, from 1920 (roughly when they first became prominent) to 2008. The graph shows a pretty steady increase of references to all three and then a tailing off, with Tatlin and Rodchenko being particularly equivalent in pattern. There is a marked peak for both around 1990 – 1991, probably related to the collapse of the Soviet Union at that time, which would have afforded Western academics increased access to their works. Also after this point many works from all three artists would have been allowed to travel abroad for the first time in decades to galleries in Europe and elsewhere, generating considerable interest. Another reason for the similarities in Rodchenko and Tatlin’s graphs may be that they were both associated with the same movement, Constructivism. Many books have been written about this specific movement and both would very likely be referenced in such works.

Kazimir Malevich has followed a somewhat different trajectory, remaining a prominent subject for discussion well into the 21st century. He is associated with a separate movement, Suprematism, in which he is by far the most notable figure. He was himself a prolific writer, and among the reasons for his increased popularity may have been the publication in the late 1990s of several volumes of his writings with English translations. There was a major exhibition of his work in Paris in 2002, followed by major retrospectives in Berlin and New York in 2003 and 2004. Such exhibitions generate a good deal of attention and renewed critical writing. In 2014 the Tate Modern gallery in London held a very sucessful exhibition of his work, so his prominence is likely to continue for some time.

I wanted to experiment more with the data from the Google Ngram Viewer. While it’s a great source of information and a very useful tool, I wanted to be able to play around with how the information looks visually, especially given my interest in fine art and aesthetics. There are many good tools available for data manipulation, but I was keen to try a more hands-on approach, so I decided to use the open-source programming language Processing, specifically developed for coding within the context of visual arts. Since my dissertation is likely to heavily feature its use, I also needed to gather more experience with it.

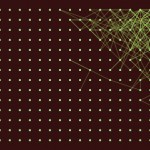

The above diagram was generated with Processing, and contains the same data from the ngram viewer with a different visual approach. The first task was to get hold of the raw data from the graph. Google Ngram Viewer doesn’t appear to have any means to be able to download the data from an individual graph, but I discovered that by viewing the source code of the webpage, the data existed as a distinct array for each search term on the graph. I was then able to insert the information into three separate arrays in my own code. This was a useful exercise as I hadn’t used or written an array before, and I understand the use of arrays will be important to produce sketches with good quality interactivity as I intend to do.

I used the data from the arrays with a for loop to draw the bars with varying length. For clarity, I retained the same colour scheme for each artist used on the Google graph, though I adjusted and desaturated them for aesthetic reasons. I also tied the opacity of each bar to its length, so the colour fades out with lower values, allowing the ones behind to be seen. This also produced a subtle modulation of colour across the graph. Finally I added a couple of for loops to produce gradients in the background for a little more atmosphere, and to contrast with the rigid geometry of the bars.

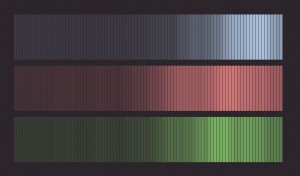

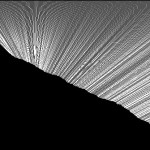

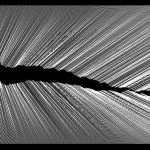

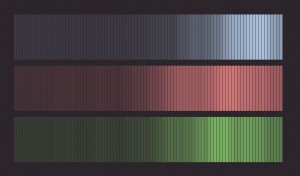

I was particularly interested in the variation in opacity I was able to get from the data, so decided to write another sketch to exploit this further, seen in the diagram above. Here, there is no variation in the length of the bars, but the difference in tone against the dark background has been exaggerated to produce a sort of contour effect.

My visualisations currently have no textual information of course, so arguably have less functional use than the original Google graph. However, in visual form all the raw information is still present, and my goal was to focus on the aesthetics to produce something which could on some level be thought of as an art piece. This was a good learning exercise. It was fascinating to see that when you have the ability to acquire and properly store and retrieve information, it gives you a lot of control over how you present it.